History of Ex-libris

Hasip Pektaş

Researchers, the first and oldest example of exlibris BC. It was made on a light blue tile in 1400 BC, and the Egyptian king III. They explain that it belongs to the library of Amenhotep (aka Pharaoh Amenhophis III). 62 x 38 x 4.5mm. It is estimated that this slab in the size of a tree was attached to the wooden crates used to protect the papyrus rolls. Ex-librisin, which has a very long tradition, dates back to BC. It is also said to be from the time of the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal, who lived around 600 BC and attached great importance to culture and art.

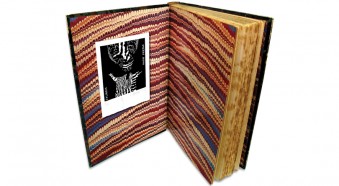

Before Gutenberg invented the printing press in the mid-15th century in Europe, books were written by hand in monasteries. Owners of hand-written limited edition books have sometimes made it a habit to put crests on the inside of the cover of the book in accordance with their own characteristics. These books were even chained to the legs of the tables in the libraries for fear of being stolen. With the proliferation of libraries with Gutenberg, the need for exlibris increased even more.

It is known that the first ex-libris was used in Southern Germany in the third quarter of the 15th century. According to the researchers, two of them were made in the name of the book owners Hildebrand Brandenburg and Wilhelm von Zell. These ex-libris consist of a simple hand-painted coat of arms and a word written by the owner’s hand. In the article; It is implored to pray for the souls of the owners of these books, which were donated to the Buxheim Abbey in Germany. The size of the ex-libris depicting an angel holding a shield with an ox with a ring on its nose, also known as the Brandenburg family crest; It is 63.5 x 63.5 mm. Made between 1470-1480, this unwritten ex-libris was printed on waste paper and colored by hand.

Another of the first ex-libris belonging to the same period is the ex-libris, which was made in 1450 for the German priest Johannes Knabensberg, known by the nickname “Igler” / hedgedog (German hedgedog), which depicts a hedgehog biting a flower in the meadow. The words “Hanns Igler, the hedgehog may kiss you” (Hans Igler das dich ein Igel kuss) are inscribed in a band at the top of the exlibris. The aim is to humorously remind the borrower that when he returns the book, he will be rewarded with a kiss, otherwise he will be the target of the hedgehog’s arrows. This first ex-libris, which was made with black ink but turned brown after centuries, is larger than today’s standard sizes; It is 190 x 140 mm.

Ex-libris, which lived its golden age in Germany in the 16th century, was also seen in other European countries in the same century. In England, the first ex-libris was made for Thomas Cardinal Wolsey in the early 1500s and for Sir Nicholas Bacon in 1574; In France, it was determined that it was made for Jean Bertaud in 1529 and for Charles Ailleboust, the bishop of Autun in 1574. The first ex-libris seen in America are those made for Henry Dunster in 1629 and for Stephen Daye in 1642 (Keenan, 2003, p.13). Ex-libris was seen in Portugal in 1585 and in Spain in 1588. It originated in Italy in the 18th century.

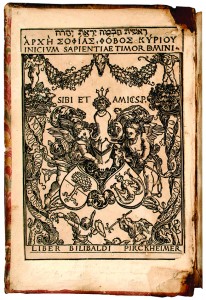

Ex-libris, which became widespread with the proliferation of books since the 16th century, was also made by famous artists. It is known that Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) made a twenty-one page ex-libris for the famous statesman and scientist of the time Willibald Pirckheimer and Hektor Pömer until 1525. Albrecht Dürer painted grapes and wine inside the horn, which is a symbol of fertility, in the heraldry he made with woodcut technique for his friend Willibald Pirckheimer. Albrecht Dürer also used the inscription “SIBI ET AMICIS”, which means “for himself and his friends”, in this ex-libri of the generous Pirckheimer; so that Pirckheimer’s friends could also benefit from these books. The Latin word “LIBER” in front of the name means “Willibald’s books”. Later, the word Ex Libris was used instead of Liber. The size of this ex-libris made before 1503 is 149 x 119 mm. It is possible to see the engraving ex-libris (181 x 100 mm) made by Albrecht Dürer for Willibald Pirckheimer in 1524 and which includes his portrait, in the books of the Pirckheimer Library in the British Museum.

In addition to Albrecht Dürer, a group of artists known as “little teachers” made ex-libris at the request of their friends and book lovers. The reason why they are called small is because what they do is small in size. Also; Lucas Cranach (1472-1553), Hans the Elder Burkhmair (1473-1531), Hans Baldung (Grien) (1484-1545), Hans Holbein (1497-1543), Barthel Beham (1502-1540), and Jost Amman (1539- 1591) is one of the important names of those periods when this art was at its peak.

Ex-libris, which differs according to various tendencies and social environment, was made for monasteries, churches, priests, princes and wealthy families with very important libraries in 17th century Germany. Some book owners stuck these small leaves with their names on their books, while others just used them as coats of arms. Especially a group of book owners in Southern Europe had reliefs, signs and coats of arms called “supra libros” made by pressing on leather-covered book covers.

Ex-libris contained more emblems from its emergence to the first half of the 17th century. From the Middle Ages, weapons, armor, and shields had distinctive markings that allowed the cavalry hidden inside to be recognized even from afar. These weapons and materials were accepted among the cultured people of the library as a sign of ownership or a pennant that more quickly identified the owner of the book. There was no need for an inscription to indicate the person’s name. This can be attributed to the reason for the preference for rigging-themed ex-libris at that time. The original woodcut made by Swiss engraver Jost Ammann for Melchior Schedel in 1570 may not be considered an ex-libris at first glance, at 35.4 x 24 cm. This ex-libris, which looks like a coat of arms, was later used by a family member with a name change (by writing Sebastian instead of the first name) and colored by hand.

Ex-libris, which was not very popular in France until the middle of the 17th century, reappeared in the 18th century with the development of the art of bookbinding. Meanwhile, many famous people were also interested in this art. XV. Luis and his favorite Marquise of Pompadour, Chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, President Henault, Writer Count de Mirabeau, etc., had ex-libris made.

Until the 20th century, many weaves (motifs) were included in the ex-libris. Crests were the most used knitting patterns until the 19th century. On top of these, a maxim or password is added alongside the owner’s name. In the 15th century ex-libris, the influence of Gothic style writings can be seen. In the 16th century, under the influence of the Renaissance, the surrounding of the coat of arms was decorated with architectural patterns and frames. In addition, typographic and portrait-oriented ex-libris have also emerged.

The influence of the Baroque period was seen in the 17th century ex-libris. Paintings were made on religious and erotic subjects, and descriptions and decorations began to be used more. While only architectural figures were used in the past, little angel pictures, figures and flowers from nature started to be used with the influence of the Italian style over time. In addition to the “crest of nobility”, where the profession of the orderer is easily understood, there was also an attitude suitable for the understanding of life.

From the 18th century onwards, nature and interior descriptions were directed, and these spaces were sometimes depicted as fantastic elements, sometimes as images from the library where the book was located. Some of the ex-libris of this period were decorated with sea shells and spiral flower braids in accordance with the artistic understanding of that day.

Ex-libris, which initially consisted of a simple name and symbol, was among the indispensable applications of large libraries at the end of the 18th century. From time to time, there are also studies that integrate with handwritten notes on the cover of the book.

The existence of the book was strengthened with the industrial revolution in the 19th century, and the foundations of scientific, economic development and intellectual change were laid with the invention of fast printing technology. Not only private libraries were developed, but large libraries were also established. An unprecedented number of books began to be produced. With the increase in book printing, simple seals, stamps and ex-libris have begun to be used in a narrower sense, instead of the designs specific to each book and book owner. However, despite everything, different trends and original studies that vary according to the social environment have always been seen.

At the end of the 19th century, there was a new revival in the art of ex-libris, and even mass-oriented studies were carried out. In this period, ex-libris collection was discovered and became widespread. Antique dealer Heinrich Lempertz from Cologne can be cited as the pioneer of this field. Lempertz published the ex-libris he collected in 1850 in a book called “Picture Books on the History of the Book Trade, Arts and Professions”. In those years, interest in old German art and the works of the “Heraldic Exlibris” (Heraldic Coat of Arms), which was about to be forgotten, increased again. Ex-libris, which is no longer made with the idea of sticking it on books, but also started to be used as objects of accumulation and exchange, has become independent as an original graphic work, rather than a book-specific sign. Theoretical research on this subject began, books and magazines were published, and associations where collectors gathered were established.

In 1880, “A Guide to Ex-libris Studies”, also known as “Warren’s Guide”, was prepared by J. Leicester Warren, later known as the Lord of Tabley, in England; artists, ex-libris classification and old examples are included. (Castle, 1893, p. 16). And eleven years later, in 1891, the first collectors’ association called “Ex-libris Society” was established in London. (Butler, 1990, p. 10). Ex-libris associations established in Germany in 1891, in France in 1894, in Switzerland and Italy in 1908, and in Belgium in 1918, provided important developments for ex-libris with their printed books, educational bulletins and documents. Over time, these associations multiplied, they published magazines, address lists and organized competitions so that their members could exchange ex-libris beyond the borders of the country.

The first International Ex-libris Congress was held in Kufstein, Austria in 1953. In 1954 in Lugano in Switzerland, in Antwerp in Belgium in 1955, in Frankfurt in Germany in 1956, in Amsterdam in the Netherlands in 1957, in Barcelona in Spain in 1958, held in Vienna, Austria in 1960, Leipzig, Germany, 1961, Paris, France, 1962, Krakow, Poland, 1964, and Hamburg, Germany, 1966. Congresses are officially organized by the International Federation of Amateur Ex-libris Associations (FISAE), which was founded in 1966.

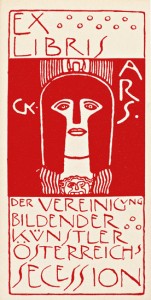

In 1900, many artists turned to new searches and reflected the styles and approaches of applied arts on ex-libris. These German artists of the new style, also called “Jugendsilkünstler”; Daniel Nikolaws Chodowiecki (1726-1801), Hans Thoma (1839-1924), Max Klinger (1857-1920), Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), Max Slevogt (1868-1932), Max Liebermann (1847-1935), Fidus di Hugo Höppene (1868-1948), Emil Orlik (1870-1932), Heinrich Vogeler (1872-1942), Alfred Kubin (1877-1959) and Franz Marc (1880-1916). These include artists such as Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Franz von Stuck 1863-1928, Fritz Erler (1868-1940), Julius Diez (1870-1957), Mathilde Ade (1877-1953) and Willi Geiger (1878-1971). can also be added. Important names of the art of painting also made ex-libris studies. The first ones that come to mind are Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Kaethe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Emil Nolde (1867-1956), Paul Klee (1879-1940), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Karl Schmidt – Rottluff (1884) -1976), Oscar Kokoschka (1888-1980) and Frans Masareel (1889-1972).

Willi Geiger, who has made many exlibris as an ex-libris artist, has also maintained his competence in the field of painting. In addition, some people from all walks of life have used eclips. Some of those; US Presidents George Washington (1732-1799), Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), writer Jack London (1876-1916), producer, director, screenwriter Walt Disney (1901-1966), actress Gloria Swanson (1899-1983) , German statesman Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), French soldier and politician Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794), British director, actor and writer Charlie Chaplin (1989-1977), philosopher William Penn (1644-1718), writer Charles Dickens (1836-1858), Queen II. Elizabeth (1926-), Scottish writer Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), Italian statesman Mussolini (1883-1945).

It is possible to create a very wide spectrum with today’s ex-libris artists. With intaglio ex-libris from Belarus Juri Jakovenko, Ivan Rusachek, Anna Tikhonova, Aleksandr Ulybin, Mirsad Konstantinovic from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Veselin Damyanov-Ves from Bulgaria, Marin Gruev, Julian Dimitrov Jordanov, Onnik Karanfilian, Hristo Naidenov, Eduard Georgiev Penkov, Peter Velikov, Jiri Brazda, Vladimir Gazovic, Robert Jancovic, Karel Zeman from Czech Republic, Lembit Löhmus, Juri Orlov from Estonia, Anneke Kuyper, Wim Zwiers from England, Peter Ford from Italy Maria Maddalena Tuccelli, Japan’s Katsunori Hamanishi, Takeshi Katori, Yukio Maekawa, Ichibun Sugimoto, Akira Tokuchou, Shigeki Tomura, Man Zhuang, Latvia’s Natalija Cernetsova, Lithuania’s Valentinas Ajauskas, Poland’s Marcin Bialas, Hanna T. Glow , Piotr Gojowy, Wojciech Luczak, Elzbieta Radzikowska, Alexei Bobrusov from Russia, Yuri Borovitsky, Olga Keleynikova, Andrey Machanov, Sergey Nesterchuk, Yuri Nozdrin, Irina Yelagina, Viladimir Zuev, Ivan Miladinovic from Serbia , from Slovakia Peter Augustovic, Igor Benca, Karol Felix, Ukraine Oleg Denisenko, Sergey Hrapov, Sergiy Ivanov, Konstantin Kalynovych, Woodcut, linoleum with high-pressure ex-libris from Germany, Ulla Günther, Axel Vater, Mauricio Schvarzman from Argentina , Austria Veronika Kyral, Ottmar Premstaller, Belgium Frank-Ivo Van Damme, Gerard Gaudaen, Mark Severin, Brazil Marcos Babtista Varela, Bulgaria Peter Lazarov, Czech Republic Miroslav Houra, Martin Manojlin, China’ den Hao Chen, Mingming Niu, Zhou Dong Shen, France’s Jean Marcel Bertrand, Polonyo’s Lukasz Cywicki, Ryszard Tobianski, Russia’s Evgenij Bortnikov, Anatolia Kalaschnikow, Valeriy Pokatov, Mikhail Verkholantsev, Ukraine’s Arkady Pugachevsky, Genna , Karel Benes, Marcel Hascic, Vladimir Suchanek from Czech Republic, Vladimir Gazovic from Slovakia, Hao Chen from China with lithograph / lithography ex-libris, Martin R. Baeyens from Belgium with silkscreen printing ex-libris, Japony Masao Ohba from a, Xiaozhuang Dong, Jing Zhang from China, Karoline Riha from Austria with computer design ex-libris, Martin R. Baeyens from Belgium, Christine Deboosere, Sylvia Dehuysser, Kurt Herman, Ann Kestens, Sophie Vael from Israel Rafi Münz, Krzysztof Marek Bak from Poland, Rastko Ciric from Serbia, Alexandrovich Vigovsky Ruslan from Ukraine are the artists that stand out.

Leave a reply